BEYOND THE WHITE CUBE

Text: OLIVER JAMESON

I. THE NEW TRADITION

"Where am I supposed to stand?” wrote Brian O’Doherty of what a spectator must ask when inhabiting the ‘white cube’ art gallery space.

The Irish installation artist, writer and critic’s book Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space is one of the most seminal writings on the type of white-walled, artificially lit art gallery that has become commonplace from the early 20th century onwards.1 In the book, which compiles a series of articles originally published in Artforum magazine, O’Doherty suggests that, in spite of its architectural implications, the white cube gallery is not a neutral space. Rather, it is a construct founded on political, economical and ideological motives; a hangover from the modernism of decades prior, from which an ornamentation and context-free venue holds art in what is supposedly its most ideal state for both viewing and purchasing.

The plain, windowless gallery space is inseparable from its intention as a place of commerce. Through the division of art from the outside world in which it was created, an object can supposedly become worthy of appreciation. The rejection of time and space can be considered less an act of preservation of the nature of the art itself, but rather one aimed at immortalising its value and desirability. On this, O’Doherty writes:

“Aesthetics are turned into commerce—the gallery space is expensive. What it contains is, without initiation, well-nigh incomprehensible—art is difficult. Exclusive audience, rare objects difficult to comprehend—here we have a social, financial and intellectual snobbery which models (and at its worst parodies) our system of limited production, our modes of assigning value, our social habits at large”.2

"Where am I supposed to stand?” wrote Brian O’Doherty of what a spectator must ask when inhabiting the ‘white cube’ art gallery space.

The Irish installation artist, writer and critic’s book Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space is one of the most seminal writings on the type of white-walled, artificially lit art gallery that has become commonplace from the early 20th century onwards.1 In the book, which compiles a series of articles originally published in Artforum magazine, O’Doherty suggests that, in spite of its architectural implications, the white cube gallery is not a neutral space. Rather, it is a construct founded on political, economical and ideological motives; a hangover from the modernism of decades prior, from which an ornamentation and context-free venue holds art in what is supposedly its most ideal state for both viewing and purchasing.

The plain, windowless gallery space is inseparable from its intention as a place of commerce. Through the division of art from the outside world in which it was created, an object can supposedly become worthy of appreciation. The rejection of time and space can be considered less an act of preservation of the nature of the art itself, but rather one aimed at immortalising its value and desirability. On this, O’Doherty writes:

“Aesthetics are turned into commerce—the gallery space is expensive. What it contains is, without initiation, well-nigh incomprehensible—art is difficult. Exclusive audience, rare objects difficult to comprehend—here we have a social, financial and intellectual snobbery which models (and at its worst parodies) our system of limited production, our modes of assigning value, our social habits at large”.2

The Irish installation artist, writer and critic’s book Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space is one of the most seminal writings on the type of white-walled, artificially lit art gallery that has become commonplace from the early 20th century onwards.1 In the book, which compiles a series of articles originally published in Artforum magazine, O’Doherty suggests that, in spite of its architectural implications, the white cube gallery is not a neutral space. Rather, it is a construct founded on political, economical and ideological motives; a hangover from the modernism of decades prior, from which an ornamentation and context-free venue holds art in what is supposedly its most ideal state for both viewing and purchasing.

The plain, windowless gallery space is inseparable from its intention as a place of commerce. Through the division of art from the outside world in which it was created, an object can supposedly become worthy of appreciation. The rejection of time and space can be considered less an act of preservation of the nature of the art itself, but rather one aimed at immortalising its value and desirability. On this, O’Doherty writes:

“Aesthetics are turned into commerce—the gallery space is expensive. What it contains is, without initiation, well-nigh incomprehensible—art is difficult. Exclusive audience, rare objects difficult to comprehend—here we have a social, financial and intellectual snobbery which models (and at its worst parodies) our system of limited production, our modes of assigning value, our social habits at large”.2

The white cube gallery space in practice. An Unlikely Friendship: John Wesley in Conversation with Donald Judd (2019) Alison Jaques Gallery, London UK

These values have long been debated and seen many opponents, but undeniably have come to prevail in dictating the way in which galleries the world over conduct their acts of business and curation. However, the emergence of virtual gallery spaces—often distributed through or design with tools conventionally used for video games—take the discussion in a new, unforeseen direction; one of increasing relevance in the face of real world uncertainty and disruption such as the global Covid-19 pandemic (an event that has informed, but not produced this article).

Be it through technology’s embrace of fantasy allowing for the creation of otherwise physically or financially impossible works, the establishment of new platforms prime for subversion or appropriation for artistic means, or the notion of video game structures dramatically shifting the act of viewing itself; the emergence of virtual space as a means of displaying artwork has provided an opportunity to boldly challenge pre-existing notions as to where and how art can exist.

These values have long been debated and seen many opponents, but undeniably have come to prevail in dictating the way in which galleries the world over conduct their acts of business and curation. However, the emergence of virtual gallery spaces—often distributed through or design with tools conventionally used for video games—take the discussion in a new, unforeseen direction; one of increasing relevance in the face of real world uncertainty and disruption such as the global Covid-19 pandemic (an event that has informed, but not produced this article).

Be it through technology’s embrace of fantasy allowing for the creation of otherwise physically or financially impossible works, the establishment of new platforms prime for subversion or appropriation for artistic means, or the notion of video game structures dramatically shifting the act of viewing itself; the emergence of virtual space as a means of displaying artwork has provided an opportunity to boldly challenge pre-existing notions as to where and how art can exist.

Be it through technology’s embrace of fantasy allowing for the creation of otherwise physically or financially impossible works, the establishment of new platforms prime for subversion or appropriation for artistic means, or the notion of video game structures dramatically shifting the act of viewing itself; the emergence of virtual space as a means of displaying artwork has provided an opportunity to boldly challenge pre-existing notions as to where and how art can exist.

II. NARRATIVE PROGRESSION

One such portrayal of a structurally divergent gallery experience is Flan Falacci’s Museum of the Saved Image (2018), a unique example of an experience that redefines the boundary between what can be considered an ‘art game’ and a ‘game as a gallery’.

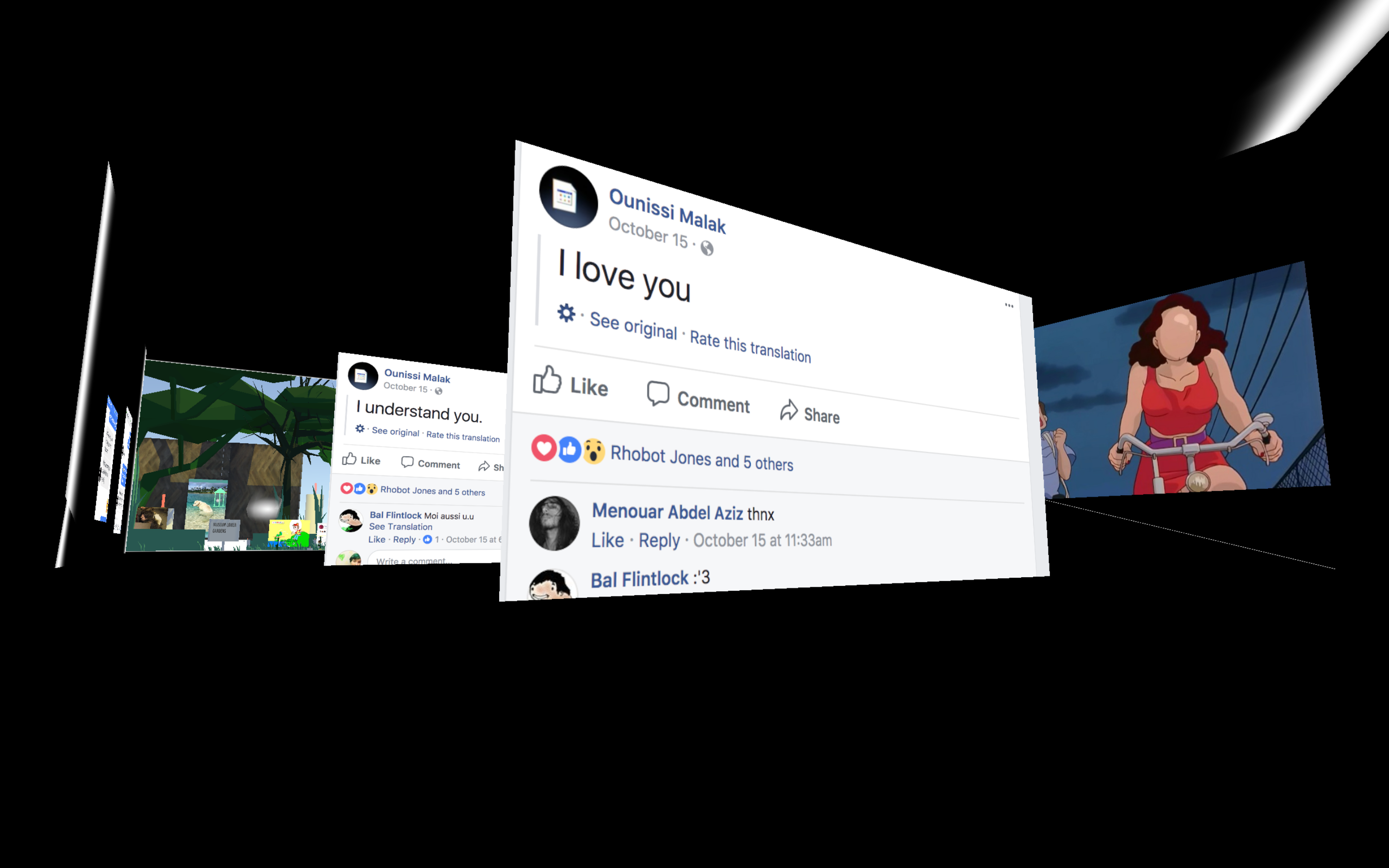

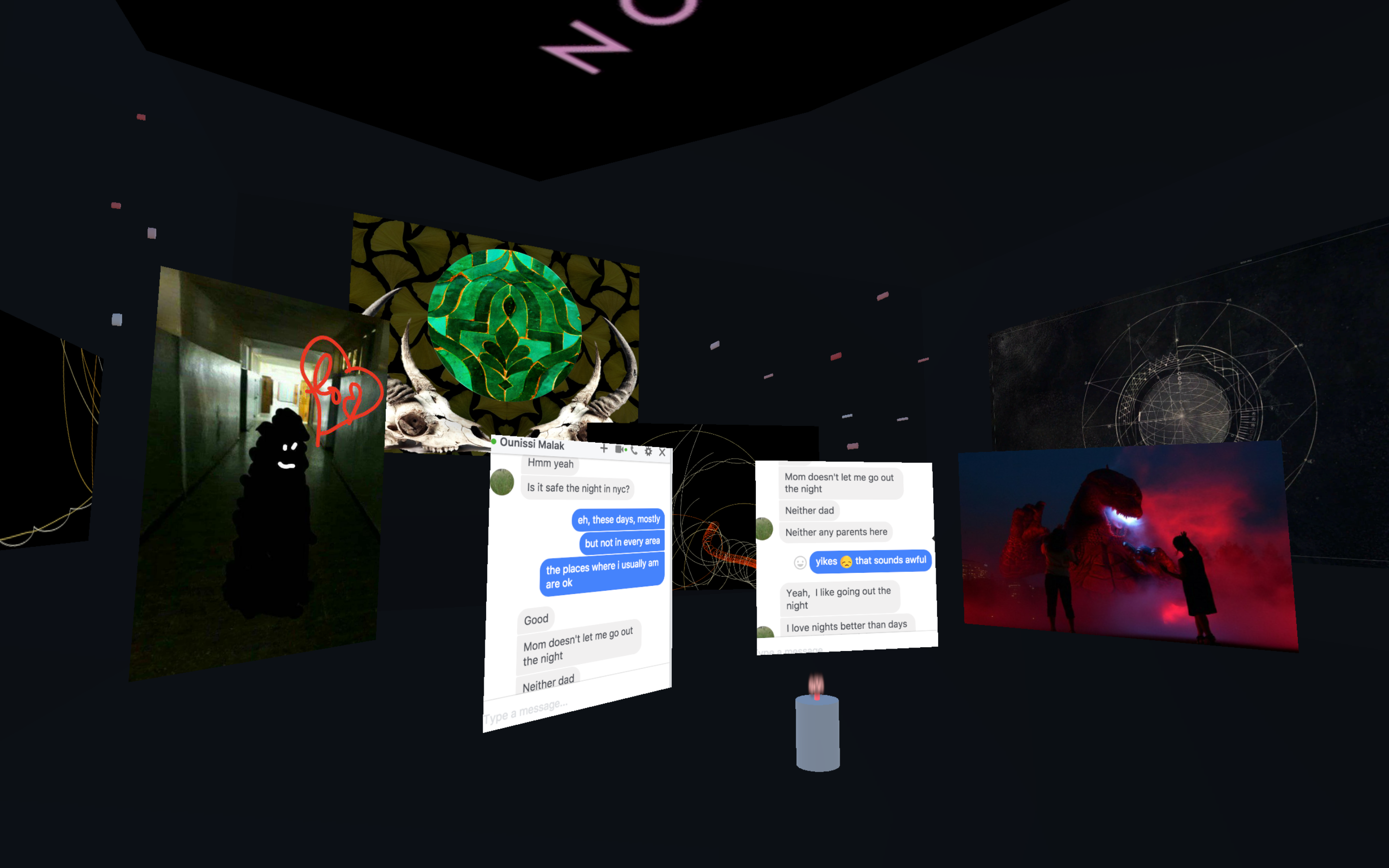

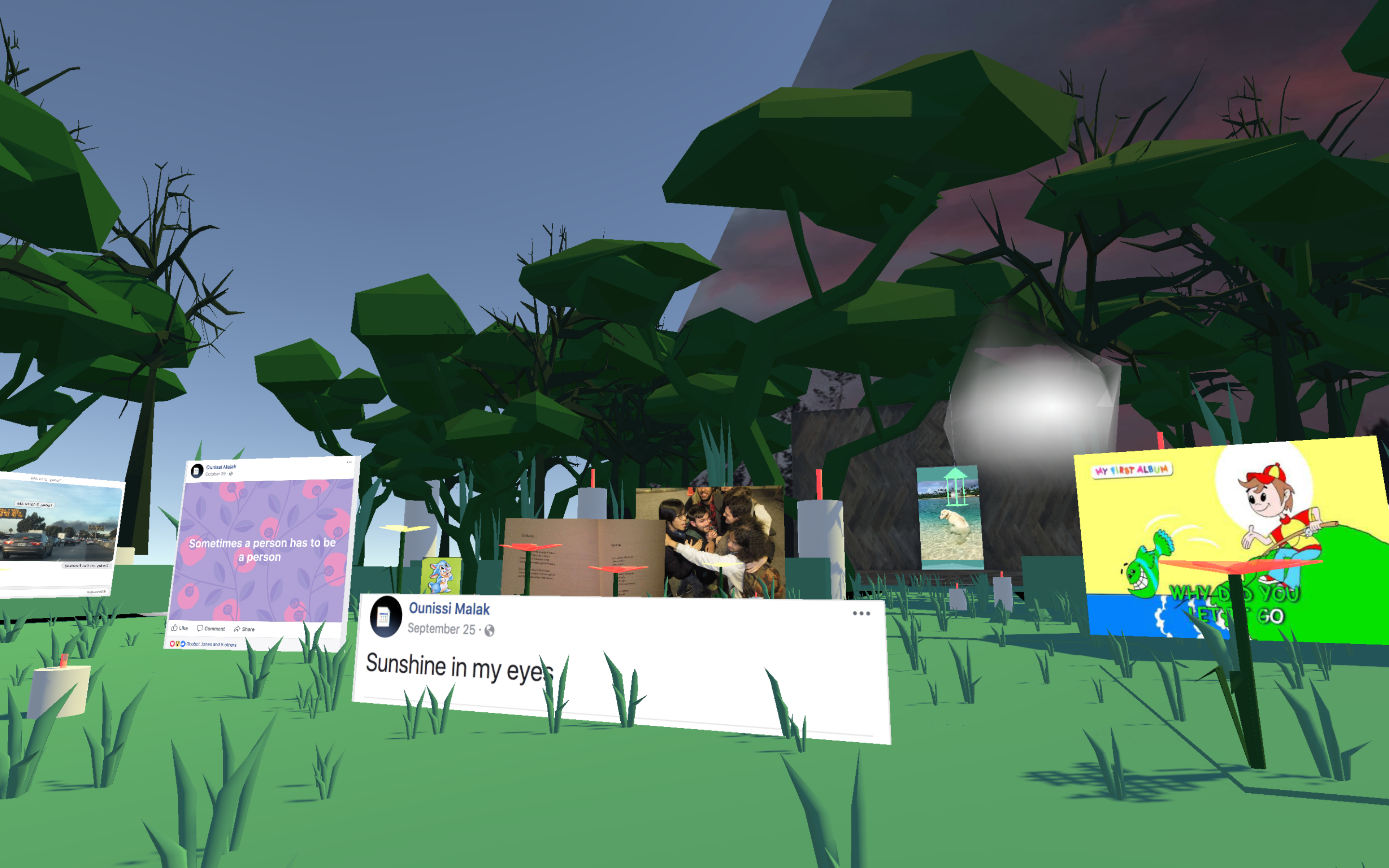

The artist presents a curated collection of images saved on their desktop within an artificial gallery setting. Loosely themed rooms divide an eclectic selection of images, ranging from memes and anime stills to photos of the artist’s friends and intimate screenshots of Facebook group chats.

Past gallery-style games such as Michael Berto and Quinn Spence’s The Zium Museum (2017)—an innovative digital group show encompassing the work of 30 artists working in different mediums—have been seen to focus on installation works designed to exist in a sole virtual space. In contrast, Falacci’s museum concerns itself with contextualising, as art, what is essentially a found object. Each image can to some extent be considered a kind of readymade, a term coined in the early 20th century by Marcel Duchamp to describe his own works created from everyday manufactured objects. The Museum of the Saved Image is a wholly 21st century readymade, collecting the often highly personal by-product of general internet and social media as its material.

Flan Falacci, Museum of the Saved Image (2018)

Falacci’s museum shares traits inherent to those of the white cube; the modernist gallery, too, is a space in which objects are contextualised as art by their surroundings. O’Doherty said of this phenomenon that “things become art in a space where powerful ideas about art focus on them. Indeed, the object frequently becomes the medium through which these ideas are manifested and proffered for discussion”.3 In physical execution, however, The Museum of the Found Image could not be further from the modernist ideal. Each room is a designed space with its own unique aesthetic elements; often these are sculptural and the museum itself is structured through a fantastical interpretation of a real world institution—for instance, food-themed saved images are held within an area labelled as the ‘Museum Cafe’, itself situated on an island amidst a sprawling body of water inhabited by colossal, cat-like icons.

In addition, images relating to a certain individual—particularly screenshots of Facebook posts and messages—are used throughout to craft a progressive narrative structure, one referenced directly by the museum’s ‘displays’. Vague enough to remain cohesive with the wider body of objects on show, the narrative successfully exists within the work, without becoming it in its entirety. If anything, such a narrative more closely resembles a motif; the near-coincidental side-effect of a personal, found object-driven curation project.

By performing these transgressions of the laws of the white cube—decrees that, whilst often unspoken, have come to define what is understood as the contemporary experience of art-viewing—the museum can be seen to effectively make use of the specific traits of its medium. A particular concern with storytelling and spatial intervention presents a possibility for an art-viewing experience that, in theory, could be transplanted into a physical gallery space, but arises naturally amidst the traditional structure of a video game.

III. SITE CONDITIONS

A challenge to the notion of the gallery-bound artwork free from outside ‘interference’ would come to the forefront of art world discourses throughout the 1970s. Artists associated with new movements, including conceptual, body, process and land art—described by artist and critic Sydney Tillim as “tactile alternatives to painting”4—would shun the traditional gallery structure, often removing themselves from it complete. From this ideological shift, the concept of site-specificity in art would arise.

Whilst the concept would be refined by a number of individuals over the decades that followed, Californian artist Robert Irwin, closely associated with the Light and Space movement, would come to be considered a key proponent of the idea of site-specific art.

When outlining ways in which to classify artworks outside of the traditional forms of painting and sculpture, Irwin described a category of art “conceived with the site in mind” in which “the site sets the parameters and is, in part, the reason for the sculpture”.5

The very essence of such an artwork, commonly presented in the form of sculptural or architectural interventions in space, challenges the predominantly modernist notion of an ideal white cube gallery space in which “the work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself”.6 A flexible term, site-specific works can essentially encompass anything from performance to land art, providing they are created so as to exist in relation to a particular place.

Many of Irwin’s site-specific works are defined by themes of awareness and encourage a shift in the perception of their surroundings. In the case of Two Running Violet V Forms (1983)—an elevated V-shaped structure of chain-link fencing coated in translucent plastic, running between the trees of a eucalyptus grove on the campus of UC San Diego—subtle contrasts and parallels are simultaneously drawn between the limitless variety of the organic treetops, the rigidity of a sculpted form and the unnatural grid formation of the human-made forest.

A challenge to the notion of the gallery-bound artwork free from outside ‘interference’ would come to the forefront of art world discourses throughout the 1970s. Artists associated with new movements, including conceptual, body, process and land art—described by artist and critic Sydney Tillim as “tactile alternatives to painting”4—would shun the traditional gallery structure, often removing themselves from it complete. From this ideological shift, the concept of site-specificity in art would arise.

Whilst the concept would be refined by a number of individuals over the decades that followed, Californian artist Robert Irwin, closely associated with the Light and Space movement, would come to be considered a key proponent of the idea of site-specific art.

When outlining ways in which to classify artworks outside of the traditional forms of painting and sculpture, Irwin described a category of art “conceived with the site in mind” in which “the site sets the parameters and is, in part, the reason for the sculpture”.5

The very essence of such an artwork, commonly presented in the form of sculptural or architectural interventions in space, challenges the predominantly modernist notion of an ideal white cube gallery space in which “the work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself”.6 A flexible term, site-specific works can essentially encompass anything from performance to land art, providing they are created so as to exist in relation to a particular place.

Many of Irwin’s site-specific works are defined by themes of awareness and encourage a shift in the perception of their surroundings. In the case of Two Running Violet V Forms (1983)—an elevated V-shaped structure of chain-link fencing coated in translucent plastic, running between the trees of a eucalyptus grove on the campus of UC San Diego—subtle contrasts and parallels are simultaneously drawn between the limitless variety of the organic treetops, the rigidity of a sculpted form and the unnatural grid formation of the human-made forest.

Whilst the concept would be refined by a number of individuals over the decades that followed, Californian artist Robert Irwin, closely associated with the Light and Space movement, would come to be considered a key proponent of the idea of site-specific art.

When outlining ways in which to classify artworks outside of the traditional forms of painting and sculpture, Irwin described a category of art “conceived with the site in mind” in which “the site sets the parameters and is, in part, the reason for the sculpture”.5

The very essence of such an artwork, commonly presented in the form of sculptural or architectural interventions in space, challenges the predominantly modernist notion of an ideal white cube gallery space in which “the work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself”.6 A flexible term, site-specific works can essentially encompass anything from performance to land art, providing they are created so as to exist in relation to a particular place.

Many of Irwin’s site-specific works are defined by themes of awareness and encourage a shift in the perception of their surroundings. In the case of Two Running Violet V Forms (1983)—an elevated V-shaped structure of chain-link fencing coated in translucent plastic, running between the trees of a eucalyptus grove on the campus of UC San Diego—subtle contrasts and parallels are simultaneously drawn between the limitless variety of the organic treetops, the rigidity of a sculpted form and the unnatural grid formation of the human-made forest.

Robert Irwin, Two Running Violet V Forms (1983)

The qualities of the site-specific are not exclusive to physical environments, however. An inherent site-specific nature is equally found in many examples of internet art, which make use of an adaptation or manipulation of pre-existing online spaces to communicate their motifs. Krystal South’s Exhibition Kickstarter (2014)—which sought to present an experimental alternative to not only a physical exhibition space, but the art market itself—utilised crowdfunding platform Kickstarter as a site for works by a selection of artists.

The exhibition embraced the concept of financial support intrinsic to Kickstarter’s purpose and design, subverting the traditional economics of the gallery by adopting a ‘supporter’ model like any Kickstarter campaign. Artworks could be purchased outright, whereas a pledge of one dollar would allow viewers to ‘follow’ the project with regular updates with interviews and writing. A percentage of every sale was used to pay the platform’s fees, as well as installation costs for a physical exhibition later that year. Tools intended for investment were creatively appropriated to achieve an ideology explained by South on the campaign page: “those who don't have thousands or millions of dollars to spend at art auctions should still be able to support artists and enjoy their artwork in their homes”.7

Whereas in the conventional sense, a site-specific artwork must be created with its venue as an integral part of the work’s plan, game spaces offer a unique contrast to this approach. Commercially available game design tools allow artists to craft unique interactive environments, through which an artwork can be presented or even created. In these cases, the question arises as to what consists of the ‘site’; a virtual, designed space in which art is presented or created, or the designed experience as a whole, with the viewer’s computer serving as a venue.

Heather Flowers’ WORLD, HARD AND COLD (2018) is described by the developer as a downloadable museum.8 An exploration game, it presents the viewer with a sequence of white-walled rooms to navigate, in which they can observe procedurally generated, plant-like sculptures gradually ‘grow’ from small geometric forms to larger structures that inhabit much of the surrounding space. The viewer’s interaction is to simply move around the space and control their line of sight, changing their perspective of the unfolding growth process and observing the way simulated light interacts with the forms. The structure and colour of each sculptures varies from room to room; with timing, it is possible to climb atop them, although this does not produce a particular response.

Aesthetically, the museum prescribes closely to the ideology of the white cube gallery, but there are fundamental differences in artistic intention.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The qualities of the site-specific are not exclusive to physical environments, however. An inherent site-specific nature is equally found in many examples of internet art, which make use of an adaptation or manipulation of pre-existing online spaces to communicate their motifs. Krystal South’s Exhibition Kickstarter (2014)—which sought to present an experimental alternative to not only a physical exhibition space, but the art market itself—utilised crowdfunding platform Kickstarter as a site for works by a selection of artists.

The exhibition embraced the concept of financial support intrinsic to Kickstarter’s purpose and design, subverting the traditional economics of the gallery by adopting a ‘supporter’ model like any Kickstarter campaign. Artworks could be purchased outright, whereas a pledge of one dollar would allow viewers to ‘follow’ the project with regular updates with interviews and writing. A percentage of every sale was used to pay the platform’s fees, as well as installation costs for a physical exhibition later that year. Tools intended for investment were creatively appropriated to achieve an ideology explained by South on the campaign page: “those who don't have thousands or millions of dollars to spend at art auctions should still be able to support artists and enjoy their artwork in their homes”.7

Whereas in the conventional sense, a site-specific artwork must be created with its venue as an integral part of the work’s plan, game spaces offer a unique contrast to this approach. Commercially available game design tools allow artists to craft unique interactive environments, through which an artwork can be presented or even created. In these cases, the question arises as to what consists of the ‘site’; a virtual, designed space in which art is presented or created, or the designed experience as a whole, with the viewer’s computer serving as a venue.

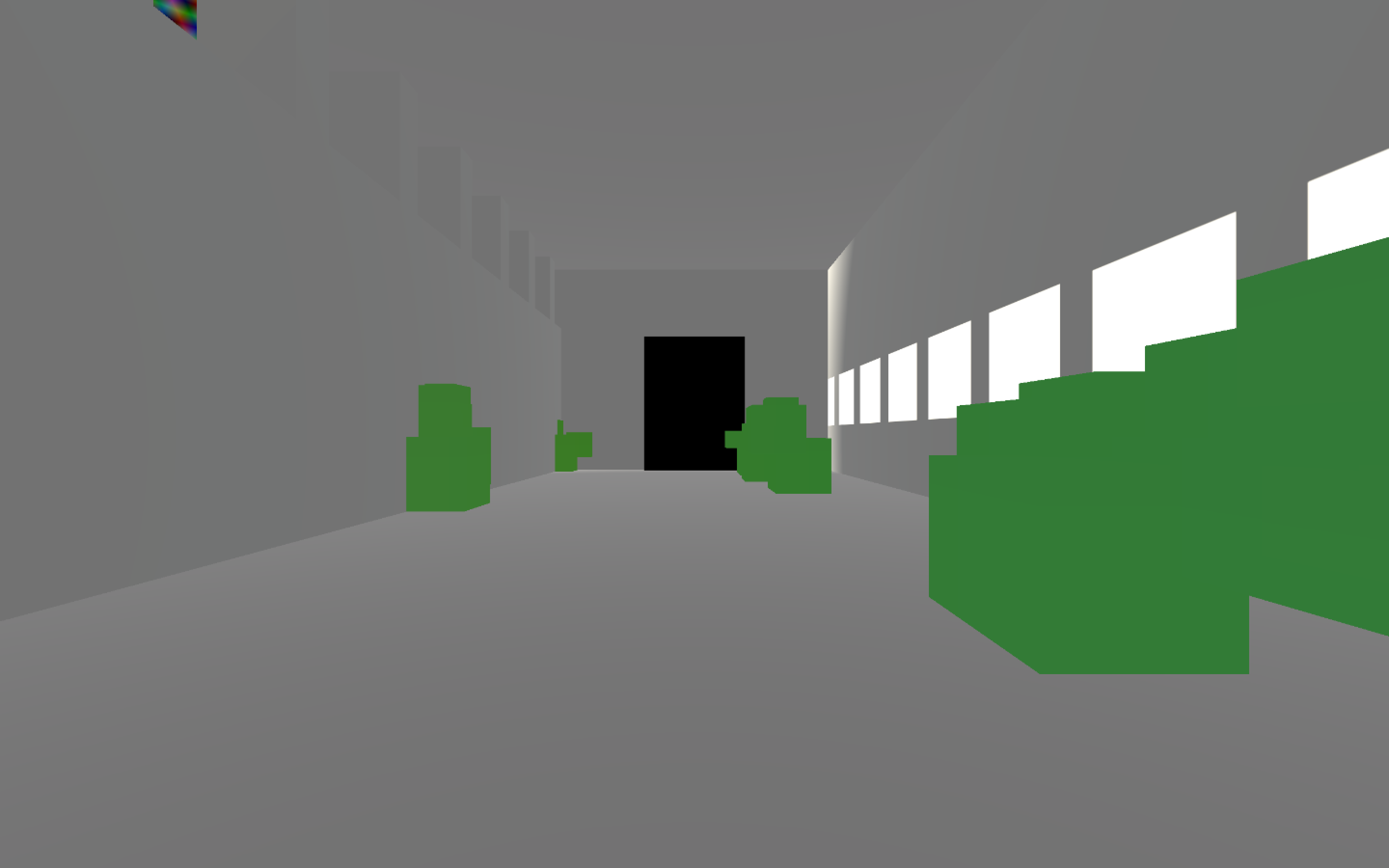

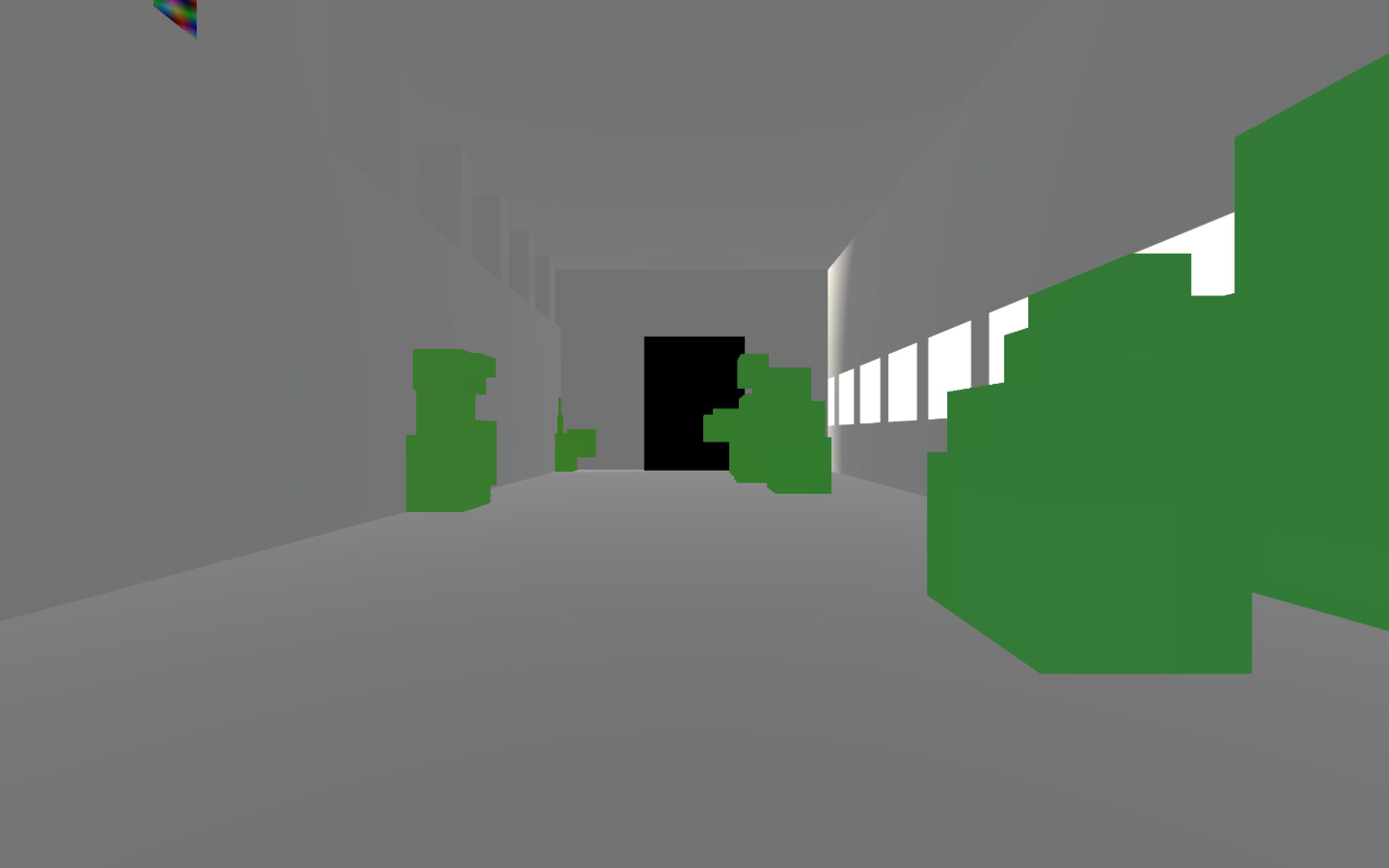

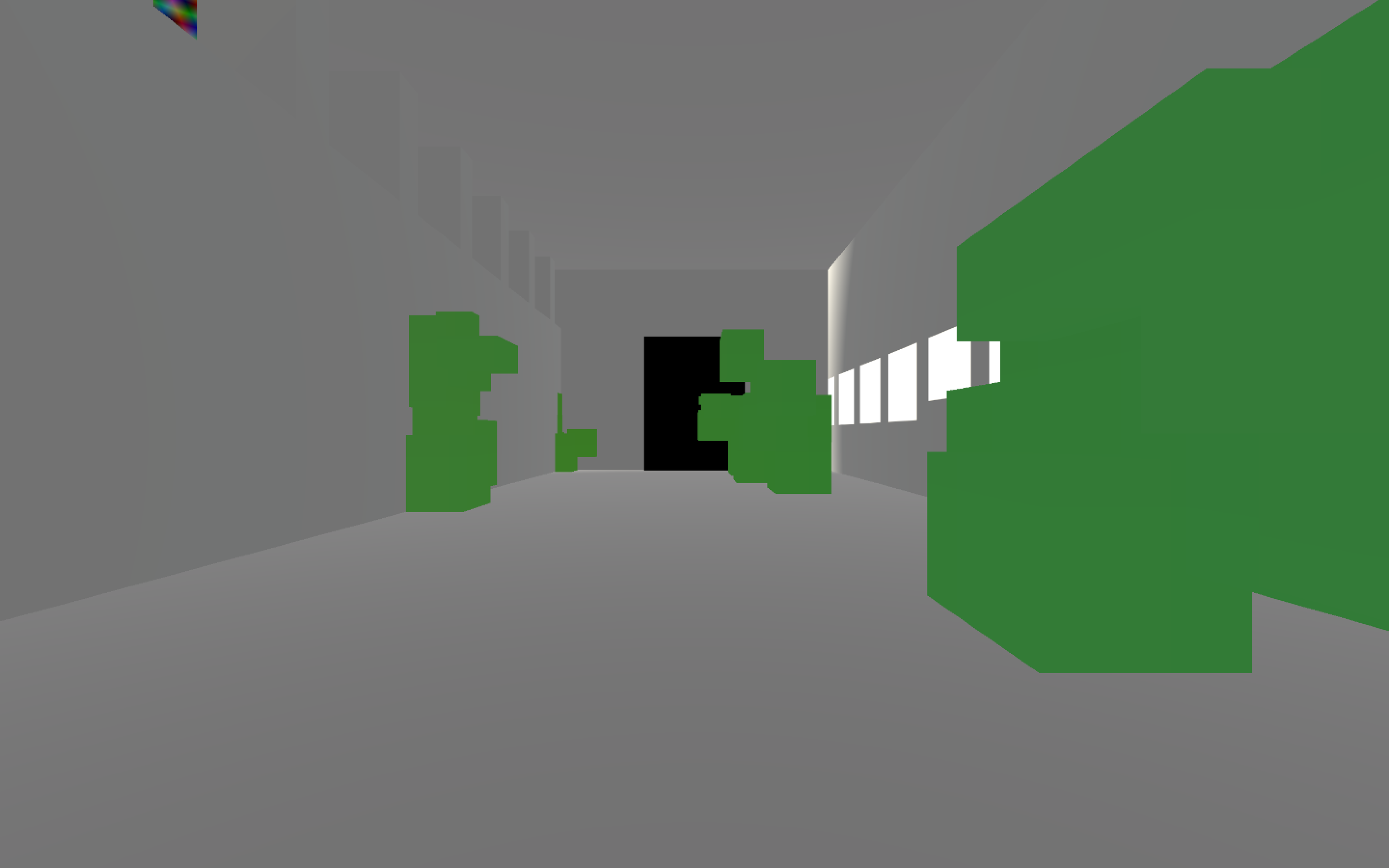

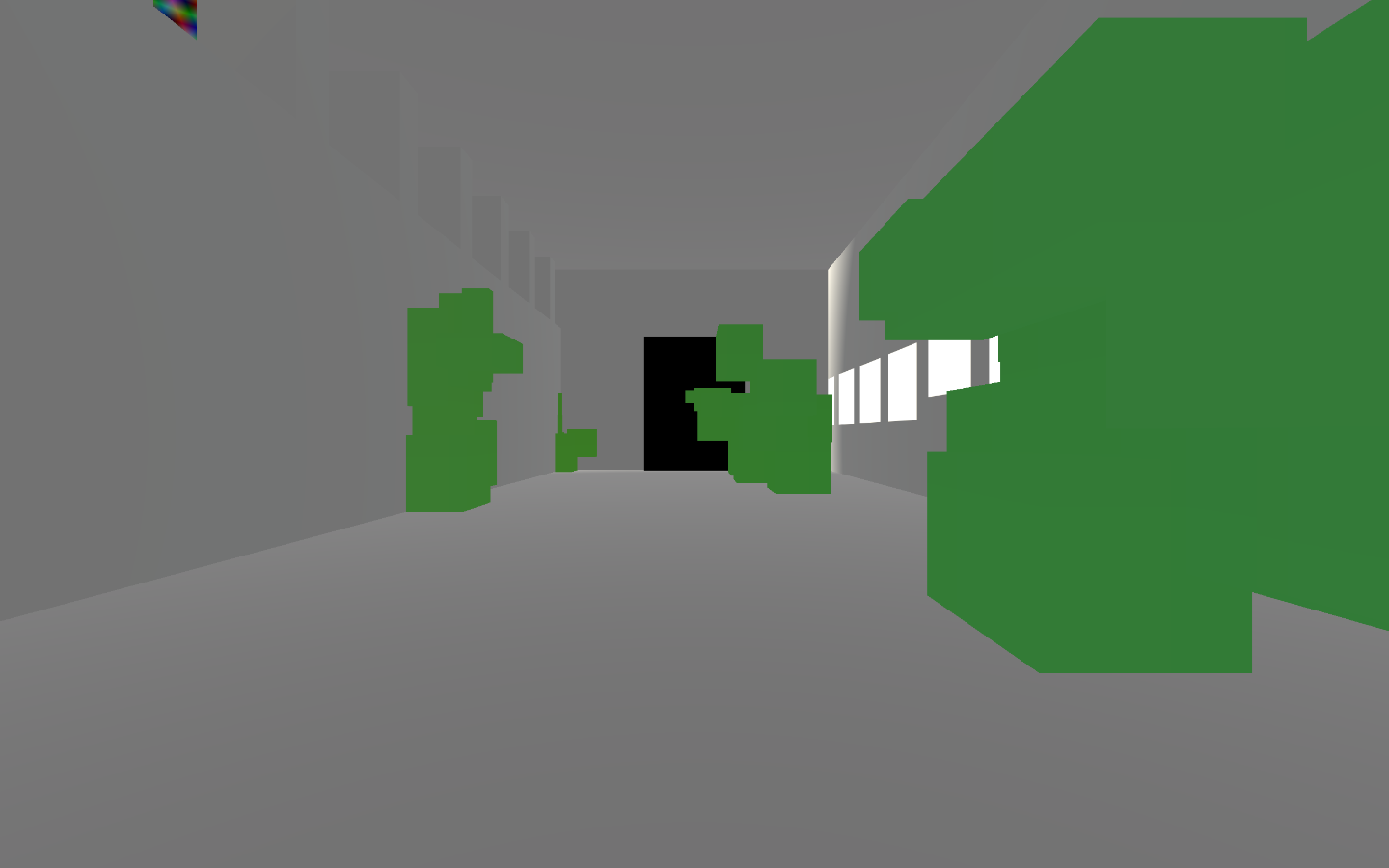

Heather Flowers’ WORLD, HARD AND COLD (2018) is described by the developer as a downloadable museum.8 An exploration game, it presents the viewer with a sequence of white-walled rooms to navigate, in which they can observe procedurally generated, plant-like sculptures gradually ‘grow’ from small geometric forms to larger structures that inhabit much of the surrounding space. The viewer’s interaction is to simply move around the space and control their line of sight, changing their perspective of the unfolding growth process and observing the way simulated light interacts with the forms. The structure and colour of each sculptures varies from room to room; with timing, it is possible to climb atop them, although this does not produce a particular response.

Aesthetically, the museum prescribes closely to the ideology of the white cube gallery, but there are fundamental differences in artistic intention.

The exhibition embraced the concept of financial support intrinsic to Kickstarter’s purpose and design, subverting the traditional economics of the gallery by adopting a ‘supporter’ model like any Kickstarter campaign. Artworks could be purchased outright, whereas a pledge of one dollar would allow viewers to ‘follow’ the project with regular updates with interviews and writing. A percentage of every sale was used to pay the platform’s fees, as well as installation costs for a physical exhibition later that year. Tools intended for investment were creatively appropriated to achieve an ideology explained by South on the campaign page: “those who don't have thousands or millions of dollars to spend at art auctions should still be able to support artists and enjoy their artwork in their homes”.7

Whereas in the conventional sense, a site-specific artwork must be created with its venue as an integral part of the work’s plan, game spaces offer a unique contrast to this approach. Commercially available game design tools allow artists to craft unique interactive environments, through which an artwork can be presented or even created. In these cases, the question arises as to what consists of the ‘site’; a virtual, designed space in which art is presented or created, or the designed experience as a whole, with the viewer’s computer serving as a venue.

Heather Flowers’ WORLD, HARD AND COLD (2018) is described by the developer as a downloadable museum.8 An exploration game, it presents the viewer with a sequence of white-walled rooms to navigate, in which they can observe procedurally generated, plant-like sculptures gradually ‘grow’ from small geometric forms to larger structures that inhabit much of the surrounding space. The viewer’s interaction is to simply move around the space and control their line of sight, changing their perspective of the unfolding growth process and observing the way simulated light interacts with the forms. The structure and colour of each sculptures varies from room to room; with timing, it is possible to climb atop them, although this does not produce a particular response.

Aesthetically, the museum prescribes closely to the ideology of the white cube gallery, but there are fundamental differences in artistic intention.

Heather Flowers, WORLD, HARD AND COLD (2018)

O’Doherty presents the white cube as a pseudo-religious venue in which value is determined and works are given material worth: “so powerful are the perceptual fields of force within this chamber”, he suggests, “that, once outside it, art can lapse into secular status”.9 WORLD, HARD AND COLD, however, is not an elitist space; with no outside world and therefore no concept of value to apply—nor any context from which the works must ‘isolate’ so as to preserve their divine status—what purpose does the white cube serve?

In this case, it is from a self-aware personification of the modernist vision of the gallery that has become so deeply embedded in the experience of art consumption that the game produces its setting, whilst simultaneously offering architecture in which the works can function on an aesthetic level. Much of the text surrounding the game—although notably absent from the game itself—alludes to this, with a simple description reading:

O’Doherty presents the white cube as a pseudo-religious venue in which value is determined and works are given material worth: “so powerful are the perceptual fields of force within this chamber”, he suggests, “that, once outside it, art can lapse into secular status”.9 WORLD, HARD AND COLD, however, is not an elitist space; with no outside world and therefore no concept of value to apply—nor any context from which the works must ‘isolate’ so as to preserve their divine status—what purpose does the white cube serve?

In this case, it is from a self-aware personification of the modernist vision of the gallery that has become so deeply embedded in the experience of art consumption that the game produces its setting, whilst simultaneously offering architecture in which the works can function on an aesthetic level. Much of the text surrounding the game—although notably absent from the game itself—alludes to this, with a simple description reading:

In this case, it is from a self-aware personification of the modernist vision of the gallery that has become so deeply embedded in the experience of art consumption that the game produces its setting, whilst simultaneously offering architecture in which the works can function on an aesthetic level. Much of the text surrounding the game—although notably absent from the game itself—alludes to this, with a simple description reading:

“explore an overgrown museum”

“hunt down color configurations”

“watch them all grow”

These three lines prescribe, in what appears to be a purposefully vague manner, the narrative motivation for the work’s setting.

The procedural sculptures themselves invoke the work of the likes of Donald Judd. Repeating structural ‘templates’ are reinterpreted in varying forms, colours and locations, developed into a self-designed ‘language’ of form.10 In this case, the work’s ‘material’—pre-programmed conditions within which the procedural forms can be generated—remain consistent throughout. However, despite their geometric forms and flat colours, the simulation of ‘growth’ witnessed in their unpredictable motion would suggest they can be considered minimalist purely in appearance.

On a technological level, these forms could, in theory, be transplanted into any number of environments, including the setting of an entirely different game. The same could be said of an Irwin sculpture; the installation Nine Spaces, Nine Trees (1983) was in fact completely reinstalled in a different location in 2007, after the building it was originally commissioned for was demolished.11 The transition largely re-contextualised the work, but physically it remained unchanged and inherited its public nature. Similarly, Flowers’ work is tied to the very nature of its format; so as to achieve their procedural effect and concern with the navigation of space, the sculptures could not exist outside of a site in the form of a game. Such a work presents a unique capacity for the use of the game as a site for artworks fundamentally connected to the place they inhabit.

These three lines prescribe, in what appears to be a purposefully vague manner, the narrative motivation for the work’s setting.

The procedural sculptures themselves invoke the work of the likes of Donald Judd. Repeating structural ‘templates’ are reinterpreted in varying forms, colours and locations, developed into a self-designed ‘language’ of form.10 In this case, the work’s ‘material’—pre-programmed conditions within which the procedural forms can be generated—remain consistent throughout. However, despite their geometric forms and flat colours, the simulation of ‘growth’ witnessed in their unpredictable motion would suggest they can be considered minimalist purely in appearance.

On a technological level, these forms could, in theory, be transplanted into any number of environments, including the setting of an entirely different game. The same could be said of an Irwin sculpture; the installation Nine Spaces, Nine Trees (1983) was in fact completely reinstalled in a different location in 2007, after the building it was originally commissioned for was demolished.11 The transition largely re-contextualised the work, but physically it remained unchanged and inherited its public nature. Similarly, Flowers’ work is tied to the very nature of its format; so as to achieve their procedural effect and concern with the navigation of space, the sculptures could not exist outside of a site in the form of a game. Such a work presents a unique capacity for the use of the game as a site for artworks fundamentally connected to the place they inhabit.

The procedural sculptures themselves invoke the work of the likes of Donald Judd. Repeating structural ‘templates’ are reinterpreted in varying forms, colours and locations, developed into a self-designed ‘language’ of form.10 In this case, the work’s ‘material’—pre-programmed conditions within which the procedural forms can be generated—remain consistent throughout. However, despite their geometric forms and flat colours, the simulation of ‘growth’ witnessed in their unpredictable motion would suggest they can be considered minimalist purely in appearance.

On a technological level, these forms could, in theory, be transplanted into any number of environments, including the setting of an entirely different game. The same could be said of an Irwin sculpture; the installation Nine Spaces, Nine Trees (1983) was in fact completely reinstalled in a different location in 2007, after the building it was originally commissioned for was demolished.11 The transition largely re-contextualised the work, but physically it remained unchanged and inherited its public nature. Similarly, Flowers’ work is tied to the very nature of its format; so as to achieve their procedural effect and concern with the navigation of space, the sculptures could not exist outside of a site in the form of a game. Such a work presents a unique capacity for the use of the game as a site for artworks fundamentally connected to the place they inhabit.

IV. DIGITAL (RE)DISTRIBUTION

Perhaps the most socially relevant aspect of the emergence of virtual galleries is the implications for the distribution of power amongst the ‘classifiers’ of the art world. For the many artists and artworks totally unable to access the traditional gallery structure—for reasons economic, physical or social—the accessibility of free and commercially available game development tools such as Unity has served as an alternative means through to find or even design spaces for display and distribution.

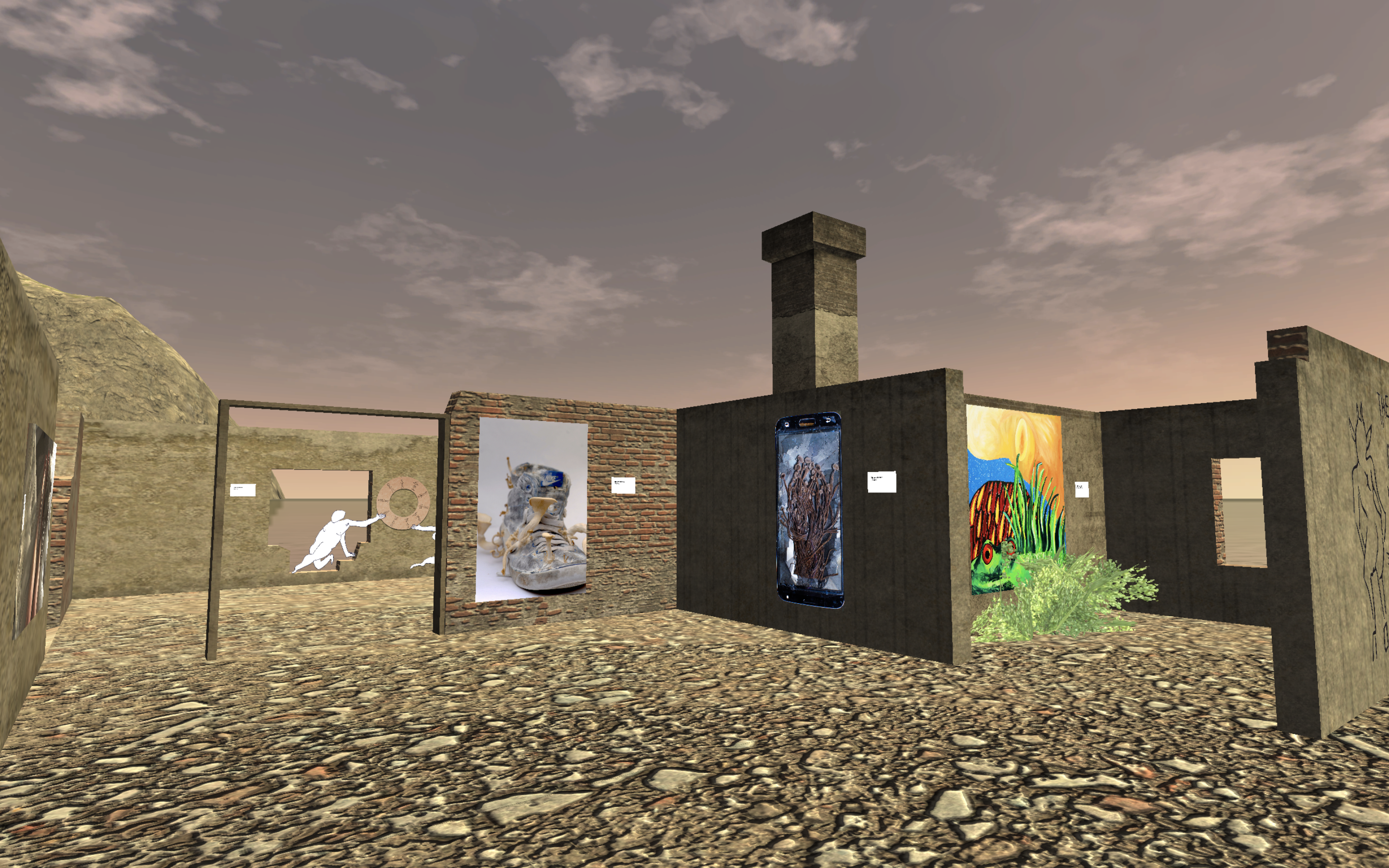

In the case of alternative fine art programme School of the Damned’s Virtual Exhibition (2019), such technologies provided an opportunity through which to share the work of a body of students lacking a fixed physical studio location. A large-scale 3D environment designed by student Molly Bliss serves as the stage for an in-game gallery space, hosting digital recreations of paintings, sculptures and video works. Like previously discussed virtual gallery examples, interactivity takes the form of simply observing.

Perhaps the most socially relevant aspect of the emergence of virtual galleries is the implications for the distribution of power amongst the ‘classifiers’ of the art world. For the many artists and artworks totally unable to access the traditional gallery structure—for reasons economic, physical or social—the accessibility of free and commercially available game development tools such as Unity has served as an alternative means through to find or even design spaces for display and distribution.

In the case of alternative fine art programme School of the Damned’s Virtual Exhibition (2019), such technologies provided an opportunity through which to share the work of a body of students lacking a fixed physical studio location. A large-scale 3D environment designed by student Molly Bliss serves as the stage for an in-game gallery space, hosting digital recreations of paintings, sculptures and video works. Like previously discussed virtual gallery examples, interactivity takes the form of simply observing.

In the case of alternative fine art programme School of the Damned’s Virtual Exhibition (2019), such technologies provided an opportunity through which to share the work of a body of students lacking a fixed physical studio location. A large-scale 3D environment designed by student Molly Bliss serves as the stage for an in-game gallery space, hosting digital recreations of paintings, sculptures and video works. Like previously discussed virtual gallery examples, interactivity takes the form of simply observing.

Molly Bliss, School of the Damned Virtual Exhibition (2019)

In the School of the Damned’s interpretation of a game space as a venue for art, a vast open-world area exists outside of the ‘gallery’ in which art is displayed. This area can be accessed by the viewer should they seek to circumvent the ‘purpose’ of the game as a whole (a venue for viewing art), but it is unclear if this is an intentional part of its design. The example allows questions to arise as to whether virtual spaces in which art is displayed can be considered works themselves; particularly in the case of areas with a structurally or architecturally unclear purpose. Similar questions could arguably be raised concerning the sculptural elements of the aforementioned Museum of the Saved Image, but the game’s narrative order contextualises these components, making their status as an artwork less ambiguous.

Accessibility is the prime concern of this instance of the virtual gallery space. With almost fantasy-like design features—the gallery inhabits a simulated wooden shack amidst a vast body of water and a rolling valley of hills—this, in essence, can be seen as something of an antithesis to the practice and ideology of the white cube, of which O’Doherty said: “never was a space, designed to accommodate the prejudices and enhance the self-image of the upper middle classes, so efficiently codified”.12 Here, in an artist-controlled space, self-expression manifests in the design of the space itself, not merely through works confined to a space shaped by values of a separate social experience.

Big Rat Studio’s digital exhibitions HANDS IN THE DIGIT(AL) AGE (2020) and I’M MAKING THIS FOR THE RAT THAT LIVES UNDER MY OVEN (2020) present a similar take on the simulated art-viewing, with digital versions of works of a variety of mediums embedded into a designed space.

In the School of the Damned’s interpretation of a game space as a venue for art, a vast open-world area exists outside of the ‘gallery’ in which art is displayed. This area can be accessed by the viewer should they seek to circumvent the ‘purpose’ of the game as a whole (a venue for viewing art), but it is unclear if this is an intentional part of its design. The example allows questions to arise as to whether virtual spaces in which art is displayed can be considered works themselves; particularly in the case of areas with a structurally or architecturally unclear purpose. Similar questions could arguably be raised concerning the sculptural elements of the aforementioned Museum of the Saved Image, but the game’s narrative order contextualises these components, making their status as an artwork less ambiguous.

Accessibility is the prime concern of this instance of the virtual gallery space. With almost fantasy-like design features—the gallery inhabits a simulated wooden shack amidst a vast body of water and a rolling valley of hills—this, in essence, can be seen as something of an antithesis to the practice and ideology of the white cube, of which O’Doherty said: “never was a space, designed to accommodate the prejudices and enhance the self-image of the upper middle classes, so efficiently codified”.12 Here, in an artist-controlled space, self-expression manifests in the design of the space itself, not merely through works confined to a space shaped by values of a separate social experience.

Big Rat Studio’s digital exhibitions HANDS IN THE DIGIT(AL) AGE (2020) and I’M MAKING THIS FOR THE RAT THAT LIVES UNDER MY OVEN (2020) present a similar take on the simulated art-viewing, with digital versions of works of a variety of mediums embedded into a designed space.

Accessibility is the prime concern of this instance of the virtual gallery space. With almost fantasy-like design features—the gallery inhabits a simulated wooden shack amidst a vast body of water and a rolling valley of hills—this, in essence, can be seen as something of an antithesis to the practice and ideology of the white cube, of which O’Doherty said: “never was a space, designed to accommodate the prejudices and enhance the self-image of the upper middle classes, so efficiently codified”.12 Here, in an artist-controlled space, self-expression manifests in the design of the space itself, not merely through works confined to a space shaped by values of a separate social experience.

Big Rat Studio’s digital exhibitions HANDS IN THE DIGIT(AL) AGE (2020) and I’M MAKING THIS FOR THE RAT THAT LIVES UNDER MY OVEN (2020) present a similar take on the simulated art-viewing, with digital versions of works of a variety of mediums embedded into a designed space.

Big Rat Studio, HANDS IN THE DIGIT(AL) AGE (2020)

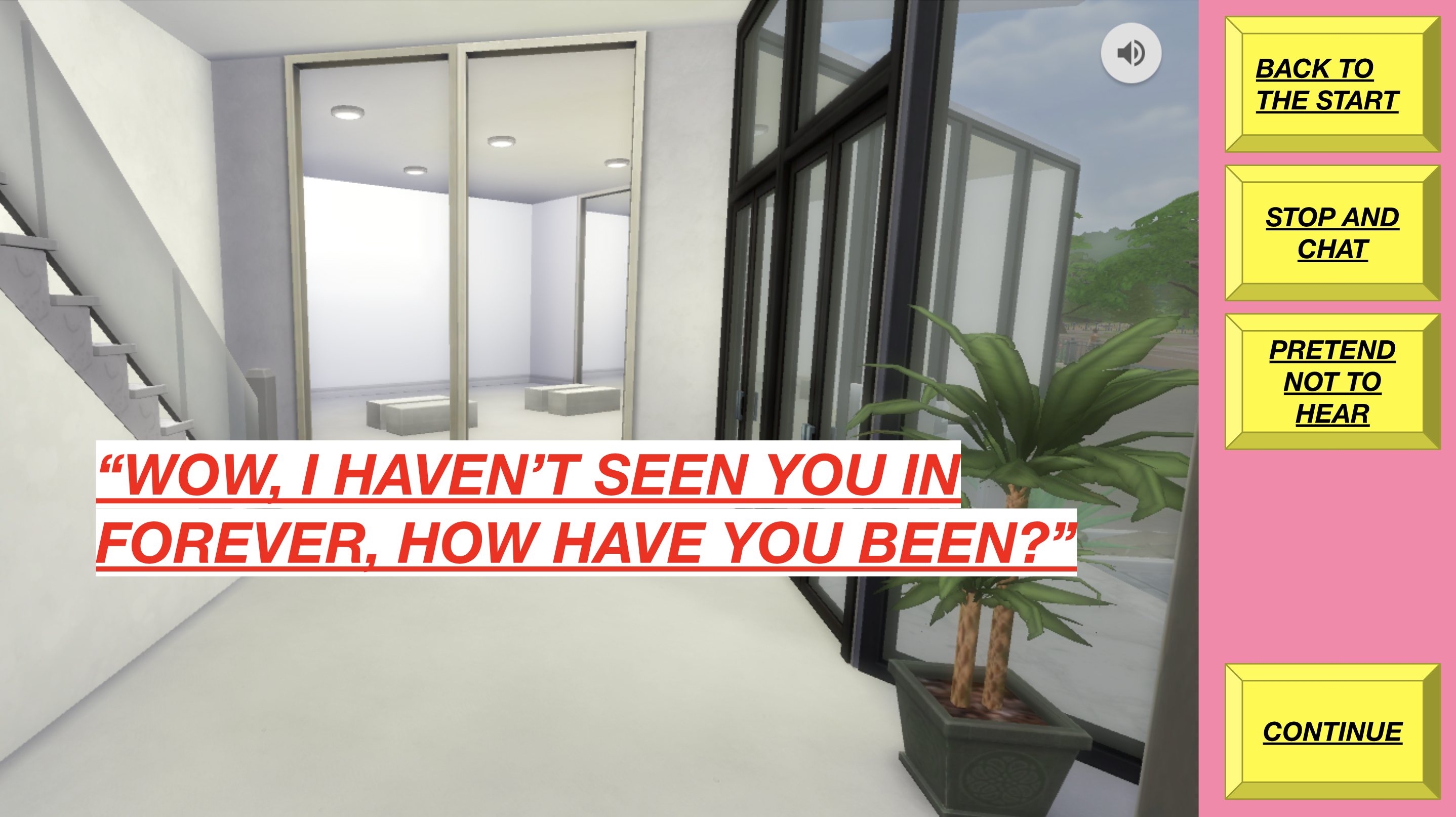

Founded by Molly Stredwick and Elliot Martin, the studio’s work is additionally a confirmation that conforming to existing game creation methods is not a requirement for achieving a coherent interactive experience. Recreated artworks are placed within environments designed in Maxis’ The Sims 4 (2014) and edited in Photoshop; an adaptation of game spaces to suit the needs of the artist that invokes many internet art subversions of existing platforms. The still images are then arranged using Google Slides, with navigational buttons offering a sense of choice in the viewer’s movement through the gallery.

Stredwick says of their approach: “it’s really low-fi but it’s working for us. The first show we made was just inspired by typical white wall galleries and we thought it was funny to use this massive gallery that in the real world wouldn’t be available to us. For the second show I worked with one of my friends and we were thinking about stuff that wouldn’t be available to us in the real world, the shows are quite fun and light hearted so we just ended up making a giant hand”.

Stredwick cites law professor Julie E. Cohen’s suggestion that cyberspace “is a space neither separate from real space nor simply a continuation of it”13 as relevant to the studio’s practice. She elaborates: “I think this applies to the galleries we make. They can be simultaneously continuous (the gallery is on a laptop in their room) and discontinuous (the gallery itself bears no relation to their room)”. As in previously discussed examples of the medium, this alludes to an inherent site-specificity, but one divergent in nature to that available to the traditional, physical artwork. The nature of an online show—initially a response to the implementation of lockdown policies in response to the Covid-19 pandemic—results in direct engagement with the ideology of gallery space. For Stredwick and Martin, humour serves as a valuable tool for exploring and challenging gallery conventions, particularly those relating to accessibility.

Founded by Molly Stredwick and Elliot Martin, the studio’s work is additionally a confirmation that conforming to existing game creation methods is not a requirement for achieving a coherent interactive experience. Recreated artworks are placed within environments designed in Maxis’ The Sims 4 (2014) and edited in Photoshop; an adaptation of game spaces to suit the needs of the artist that invokes many internet art subversions of existing platforms. The still images are then arranged using Google Slides, with navigational buttons offering a sense of choice in the viewer’s movement through the gallery.

Stredwick says of their approach: “it’s really low-fi but it’s working for us. The first show we made was just inspired by typical white wall galleries and we thought it was funny to use this massive gallery that in the real world wouldn’t be available to us. For the second show I worked with one of my friends and we were thinking about stuff that wouldn’t be available to us in the real world, the shows are quite fun and light hearted so we just ended up making a giant hand”.

Stredwick cites law professor Julie E. Cohen’s suggestion that cyberspace “is a space neither separate from real space nor simply a continuation of it”13 as relevant to the studio’s practice. She elaborates: “I think this applies to the galleries we make. They can be simultaneously continuous (the gallery is on a laptop in their room) and discontinuous (the gallery itself bears no relation to their room)”. As in previously discussed examples of the medium, this alludes to an inherent site-specificity, but one divergent in nature to that available to the traditional, physical artwork. The nature of an online show—initially a response to the implementation of lockdown policies in response to the Covid-19 pandemic—results in direct engagement with the ideology of gallery space. For Stredwick and Martin, humour serves as a valuable tool for exploring and challenging gallery conventions, particularly those relating to accessibility.

Stredwick says of their approach: “it’s really low-fi but it’s working for us. The first show we made was just inspired by typical white wall galleries and we thought it was funny to use this massive gallery that in the real world wouldn’t be available to us. For the second show I worked with one of my friends and we were thinking about stuff that wouldn’t be available to us in the real world, the shows are quite fun and light hearted so we just ended up making a giant hand”.

Stredwick cites law professor Julie E. Cohen’s suggestion that cyberspace “is a space neither separate from real space nor simply a continuation of it”13 as relevant to the studio’s practice. She elaborates: “I think this applies to the galleries we make. They can be simultaneously continuous (the gallery is on a laptop in their room) and discontinuous (the gallery itself bears no relation to their room)”. As in previously discussed examples of the medium, this alludes to an inherent site-specificity, but one divergent in nature to that available to the traditional, physical artwork. The nature of an online show—initially a response to the implementation of lockdown policies in response to the Covid-19 pandemic—results in direct engagement with the ideology of gallery space. For Stredwick and Martin, humour serves as a valuable tool for exploring and challenging gallery conventions, particularly those relating to accessibility.

Big Rat Studio, I’M MAKING THIS FOR THE RAT WHO LIVES UNDER MY OVEN (2020)

“I think there’s something funny about having a virtual exhibition in a space that looks a bit real”, Stredwick explains. “It’s a step away from reality because we could never afford a space like that in real life. In the first show we did, we reference the fact that we had chosen to recreate a white cube gallery with the furniture and everything - including a ‘black cube’ style video room - and make jokes about it”.

As an experience detached from reality, it becomes possible for the artist to design a space that directly addresses the very venture of gallery viewing. In the case of Big Rat Studio’s exhibitions, this comes in the form of writing and sound design introspective of particular moments ingrained in the experience as a whole. Reference is made to aspects such as venue costs, alcohol consumption and social encounters entrenched in the culture of student private views. This is implemented in a manner that engages with the implicit surreality of a digital viewing—self-aware and often self-deprecating—whilst still championing the possibilities of a new format for displaying work.

“I think there’s something funny about having a virtual exhibition in a space that looks a bit real”, Stredwick explains. “It’s a step away from reality because we could never afford a space like that in real life. In the first show we did, we reference the fact that we had chosen to recreate a white cube gallery with the furniture and everything - including a ‘black cube’ style video room - and make jokes about it”.

As an experience detached from reality, it becomes possible for the artist to design a space that directly addresses the very venture of gallery viewing. In the case of Big Rat Studio’s exhibitions, this comes in the form of writing and sound design introspective of particular moments ingrained in the experience as a whole. Reference is made to aspects such as venue costs, alcohol consumption and social encounters entrenched in the culture of student private views. This is implemented in a manner that engages with the implicit surreality of a digital viewing—self-aware and often self-deprecating—whilst still championing the possibilities of a new format for displaying work.

As an experience detached from reality, it becomes possible for the artist to design a space that directly addresses the very venture of gallery viewing. In the case of Big Rat Studio’s exhibitions, this comes in the form of writing and sound design introspective of particular moments ingrained in the experience as a whole. Reference is made to aspects such as venue costs, alcohol consumption and social encounters entrenched in the culture of student private views. This is implemented in a manner that engages with the implicit surreality of a digital viewing—self-aware and often self-deprecating—whilst still championing the possibilities of a new format for displaying work.

V. FORWARD THINKING

The act of viewing art in virtual space is not yet ‘perfect’, in the traditional sense of what the experience entails. The sensory, affective and perspective-related details of certain works will undoubtedly be lost in digital translation, whereas certain works—particularly conceptual ones—may be impossible to create in a space innately separate from the physical human experience.

While there is much reason to believe that technology will some day progress in the direction of simulating these aspects in a more realistic manner, at present the game as a gallery space does well to address the art-viewing experience in a way that successfully utilises traits inherent to its medium.

Perhaps most importantly, it is a method of returning creative control to the artists themselves. Architecture, narrative structure, scale, material and audience become factors to be determined by, rather than imposed upon, the artist. The versatile potential of game design technologies and principles offers a unique opportunity to free the artist from a dominant notion of artworks absent of context and instinctively commercialised.

Through considered design, art and space can become inseparable not through material constructs but artistic intention. Space becomes not only a place for art, but potentially art itself.

The act of viewing art in virtual space is not yet ‘perfect’, in the traditional sense of what the experience entails. The sensory, affective and perspective-related details of certain works will undoubtedly be lost in digital translation, whereas certain works—particularly conceptual ones—may be impossible to create in a space innately separate from the physical human experience.

While there is much reason to believe that technology will some day progress in the direction of simulating these aspects in a more realistic manner, at present the game as a gallery space does well to address the art-viewing experience in a way that successfully utilises traits inherent to its medium.

Perhaps most importantly, it is a method of returning creative control to the artists themselves. Architecture, narrative structure, scale, material and audience become factors to be determined by, rather than imposed upon, the artist. The versatile potential of game design technologies and principles offers a unique opportunity to free the artist from a dominant notion of artworks absent of context and instinctively commercialised.

Through considered design, art and space can become inseparable not through material constructs but artistic intention. Space becomes not only a place for art, but potentially art itself.

While there is much reason to believe that technology will some day progress in the direction of simulating these aspects in a more realistic manner, at present the game as a gallery space does well to address the art-viewing experience in a way that successfully utilises traits inherent to its medium.

Perhaps most importantly, it is a method of returning creative control to the artists themselves. Architecture, narrative structure, scale, material and audience become factors to be determined by, rather than imposed upon, the artist. The versatile potential of game design technologies and principles offers a unique opportunity to free the artist from a dominant notion of artworks absent of context and instinctively commercialised.

Through considered design, art and space can become inseparable not through material constructs but artistic intention. Space becomes not only a place for art, but potentially art itself.

1 Brian O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space

2 O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube, 76

3 O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube, 14

4 Sidney Tillim (1977) Notes on Narrative and History Painting in Artforum, Vol. 15, Issue 9, 41

5 Jan Butterfield (1993) The Art of Light + Space, 52-53

6 O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube, 14

7 Krystal South (2014) Exhibition Kickstarter https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/ksouth/exhibition-kickstarter

8 Heather Flowers (2018) WORLD, HARD AND COLD https://hthr.itch.io/world-cold-and-hard

9 O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube, 14

10 Hal Foster (2020) Object Lessons in Artforum Vol. 58, Issue 9, 137

11 Gary Faigin (2008) Public Art | “Nine Spaces, Nine Trees” at University of Washington - May 2008 http://www.garyfaigin.com/art-reviews-blog/public-art-nine-spaces-nine-trees-at-university-of-washington-may-2008

12 O’Doherty (1976) Inside the White Cube, 76

13 Julie E. Cohen (2007) Cyberspace As/And Space, 213